On Nov 30, 2021, the 15-year-old Ethan Crumbley pulled out a pistol and killed four fellow students at his high school in Oakland County, Michigan (near Detroit). He was apprehended, tried as an adult, and now sits in a cell with a life sentence.

The DA (Karen D. McDonald) decided to pursue Ethan’s parents with a charge of involuntary manslaughter, for various failures in their parenting that she claims were materially causal to the slaughter. In separate trials, juries have declared both parents guilty.

School shootings have a history going back some two centuries. Probably, they were only first impressed deeply on public consciousness in 1999 with the particularly egregious Columbine massacre. But in all this history, the Crumbley case appears to be the first time such a move has been made against the parents of the shooter.

There are a number of reasons why I think the prosecution and conviction of Mr. and Mrs. Crumbley is an ominous sign for the future of American freedom.

1. Almost immediately after the incident, the police were treating the Crumbleys as virtual criminals — holding guns on them as they left the house for a search warrant; stirring up public opinion against them via the press; putting up wanted posters immediately when the Crumbleys very understandably went on the lam, including the offer of a reward.

It’s not like anyone, even this activist prosecutor, is claiming Mr. and Mrs. Crumbley were in on the plot, or had knowledge of their son’s nefarious plan. They just were not the best parents, especially by the standards of suburban soccer moms. The missus was having an affair with a local fireman, and the mister is a bit dim-witted. But especially: they owned a gun that was not kept under lock and key.

2. Disproportionate response

A dozen swat team members busted through the door in the middle of the night while the Crumbleys were sleeping, shouting and holding assault weapons on them.

We are seeing this more and more. Also in 2021, the FBI sent a goon squad of 20 heavily armed men, at dawn, in front of his family, to arrest pro-life activist Mark Houck, though he had offered to appear voluntarily.

Our rulers have trained us to react negatively to images of “Nazi stormtroopers” dressed in black and goose-stepping with jack boots to terrorize the citizenry. It is not supposed to enter our minds, that in fact our rulers are gradually creating their own jack-booted black-uniformed instruments of terror. (Our soil is magic! Our gangs of shouting, heavily-armed, jack-booted enforcers are good guys!)

Compare how far we have come from the society depicted 50 years ago in the Colombo movies, where often, in the final scene, the murder suspect is politely escorted, without handcuffs, by a single officer to the squad car. Granted, the movies were fiction. But fiction depicts an accepted reality.

3. Overbearing use of force even in the court.

At the end of the first day of testimony, the prosecution made a motion to restrict the defendant’s communications to his lawyer and “approved” clergy. They alleged that the defendant had made threatening calls from the jail. Prima facie, this is quite implausible. They did not expect to need to present testimony subject to rebuttal of their claim. They expected their mere say-so to be accepted. This was one of the most chilling moments in the whole trial.

Also — who gets to “approve” of the clergy again?

4. Manipulation of the media to whip up public sentiment. For example, pro-prosecution witness William Creer testified that when he arrived at the site of the arrest at 2 AM there was already a large contingent of media there with lights and cameras.

5. Humiliating the defendants. They show pictures of their underwear, details of their housekeeping, and so forth.

6. Dubious legal arguments of omission are brought forward that could be expanded indefinitely.

The prosecution argued that tiny, easy acts could have prevented the tragedy. For example, she demonstrated to the jury that a trigger lock could be installed in 10-12 seconds. This would bias the jury to think that what the state was demanding of the Crumbleys, and which they failed to perform, was something trivial, thus strengthening their inclination to find guilty. By doing this, the prosecutor was setting up what is called an enthymemic argument, i.e. one in which one premise is unstated. This form of argument is very powerful rhetorically; but the problem is, the unstated premise can be quite wrong. Consider that

- it was not legally required to install trigger locks

- guns that are locked up are virtually useless for home defense

- Mr. Crumbley had never claimed that it was too difficult or time-consuming to perform these acts

- lots of people, especially school officials, also could have done “one tiny thing” that would have prevented the assault

7. Worse yet, the greatest sin of omission claimed by the prosecution was failing to address and remedy the “mental health” of the child. This means nothing else than forcing on the population an acceptance of current psychological theories about human personhood, along with the counseling and drug programs that go along with it. But Christians ought not to accept these bankrupt and godless theories.

8. The case was virtually made into a federal case, though there was no interstate basis. This gave the state vast resources, including a federal SWAT team, BATF consulting, and expert witnesses. This is unfair ganging up against a citizen defendant.

It was quite disturbing to see a virtually limitless lineup of witnesses of every calling and expertise, and multiple prosecution attorneys, arrayed against the sole lawyer on the defense.

9. Taking the bird’s eye view, we see an uneven enforcement of the law

- Southside Chicago has multiple murders per week, and there is no question that there is a vast sea of bad parenting correlated to that. Yet those parents are not prosecuted.

- Nor have any of the parents of any school shooting to date.

- Nor have any of the school officials in this case been charged, even though it was quite clear from their own testimony that they had at least as much reason to intervene before the act as could be proved about the parents

- In addition, the shooter continued his rampage for almost 5 minutes after the police arrived. Again and again, we find that the cops’ first priority is their own safety, not that of the children. I remember watching the news of one shooting where the cops not only refused to go in, but physically prevented the arriving fathers from going in! There is a tremendous imbalance of taking responsibility that is exemplified in a case like this. Why are they not held responsible, ever?

Some unevenness between districts is inevitable. But it goes against the premise of common law and also allows selective prosecution if the disparity becomes this great.

10. Moreover, an inconsistent application of legal categories was applied even within this trial.

Notably, Ethan was charged as an adult, meaning he is regarded as having adult responsibilities. Yet, the parents were charged for bad parenting, which only makes sense if Ethan is regarded a minor legally. (In fact he was 15.)

This shows that our rulers are not sticking to fixed principles, but they can offer contradictory models even within the same case, when it suits their agenda.

11. There was an ironic usage of racial profiling

Did anyone notice that the trial looked like a 50’s movie racially? I can’t recall seeing more than a single Negro, and no Orientals, in a long line of witnesses, lawyers, and spectators. Notice the cleverness of this ploy: it deftly avoids the suspicion either of selective prosecution or of the “replacement” peoples exercising vengeance on the native population. This was Honky vs Honky. You can relax, reactionaries: there’s no bias going on here.

12. The legal criterion of pick-and-choose two legal theories is dubious. The jury instructions allowed the jury to convict even if half favored one theory and half another. This method was also used in the Hannah Gutierrez trial. This is a tricky subject that I will analyze in more detail in a separate post. I am just bookmarking this issue for now.

Conclusion

In the post-trial interview, the prosecutor Karen D. McDonald, a Democrat, made it clear that all my suspicions outlined above were ratified. After Rittenhouse, this prosecution was a second shot over the bow by our rulers to crimp down on effective gun ownership. Rittenhouse failed; this one succeeded. Gun grabs don’t have to be a literal confiscation. If you must either lock up your gun or be liable to jail, then you can’t have a gun for home defense.

She repeated over and over that guns are the Number One cause of deaths of “children.” As such, this is fallacious reasoning: If guns were the only cause of youth deaths, and there was only one every once in a blue moon, this would hardly have the persuasive force that her tricky rhetoric implies.

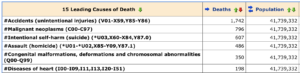

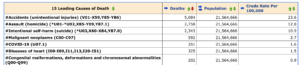

Moreover, “children” is a bit broad and ambiguous when speaking of these kinds of statistics. According to the CDC, in the 5 to 14 year old age group, accidents are the number 1 cause of death, and more than triple the number of homicides.

Both malignant neoplasms and suicides exceed the number of homicides. (The use of guns is not broken out for either suicides or homicides.)

In the 15-19 year old age group, accidents are the number 1 cause, and nearly double the count of homicides (of all weapon types).

Moreover, suicides are nearly equal in count to homicides. Our rulers do not seem nearly as concerned about that. Yes, doctors now routinely ask “are you feeling depressed?” and what not, and even McDonald herself set up some kind of “Task Force” on the subject, but we suspect all of that kind of activity is as much to get more people on psycho-tropic drugs as it is to stop suicides. If they were concerned about youth suicides, they would look within to see if their own subversive complicity is as much the problem as anything else — complicity with forces bent on destroying our nation that leave many of our youth with no prospects, and with endless vile teaching that informs them that pleasure is the greatest good.

It certainly appears that she is lying about the “number one cause of children’s deaths.”

Speaking of child abuse, the prosecutor Karen D. McDonald, a Democrat, “is especially proud to have presided over the first adoption by an LGBTQ+ couple in the history of the State of Michigan.”

This trial and the zombie-like response of the jury should be flagged as a dire milestone on the way to the “last battle” for the survival of our people and holy religion.

But I predict our snoozing clergy will not even notice.